2013 ended with a major victory for organized labor – the triumphant struggle of the Philippine Airlines Employees Association (PALEA) against outsourcing and contractualization.

2013 ended with a major victory for organized labor – the triumphant struggle of the Philippine Airlines Employees Association (PALEA) against outsourcing and contractualization.

On 14 November 2013, a settlement agreement between PALEA and the Philippine Airlines (PAL) finally ended the 26-month labor dispute that arose from the flag-carrier’s implementation of a massive outsourcing program in October 2011 (see Outsourced! article in the previous issue of InFocus).

The settlement agreement guaranteed that remaining locked-out PALEA members would regain their status as regular PAL workers, the most important element of the hard-won battle. On top of this was a financial package significantly higher than what was granted by the Department of Labor and Employment (DOLE) and the Office of the President (OP) – the two government agencies that presided over and legitimized the implementation of PAL’s anti-labor outsourcing plan.

No role

Let it be pointed out that the government played no role in the course of the negotiations, despite the issue being included as the fourth item in President Aquino’s 22-point labor agenda. PALEA did it the workers’ way. It was not Malacañang but PALEA and its supporters in Nagkaisa and the entire labor movement here and abroad that forced the new PAL owner, San Miguel Corporation (SMC), to sit at the negotiating table. It was PALEA’s 26 months of determined defiance and sustained resistance against outsourcing that saved their regular jobs. It was the protest camp of PALEA – not the Labor Department, not the Palace nor the courts – that served as fortress in the workers’ struggle for labor rights and decent work.

The government was supposed to be the guardian of labor rights as mandated by the Constitution and by virtue of its international commitments, including the International Labor Organization (ILO) conventions that it ratified. However, in the PALEA-PAL case, the government was clearly on the side of capital.

Higher power rates

On November 30, 2011, the union-initiated and consumer-backed Cooperative-to-Cooperative (C2C) option to get the ailing Albay Electric Cooperative (ALECO) out of bankruptcy was put to a vote in a General Assembly against the Private Sector Participation (PSP) option. The union was opposed to PSP not only because it will lead to price hikes due to an emerging Meralco-type relationship between the buyer and seller of power, but more so because of the fear that privatization will also lead to a Napocor-type mass retrenchment.

According to the Alliance of Progressive Labor (APL) where ALECO union is affiliated, the C2C got 355 against 155 votes for PSP. But proponents of PSP – which included the government through the Department of Energy, the National Electrification Administration (NEA) and the local government of Albay – conspired to block the C2C by calling for a referendum on September 14, 2013, where voters were bought and hauled to vote for PSP. Voters’ turnout was only 4.8%, short of the legal requirement of 5%. Yet the sham referendum that voted for PSP was certified valid by NEA and the DoE.

Under the PSP, ALECO would be effectively privatized with San Miguel Power, a subsidiary of San Miguel Corporation, taking over its operations through concession for the next 25 years. On the other hand, under C2C, ALECO would remain as a non-profit and membership-controlled utility, with sister coop, the Benguet Electric Cooperative (BENECO), providing it with technical expertise and free hardware to reduce the current system loss and improve its collection efficiency. The scheme would eventually restore ALECO’s financial viability in the span of just five years.

Unfortunately the devious government option prevailed over the more democratic, multi-sectoral, grassroots and union-backed option. The Aleco Employees Organization (ALEO) which, prior to the C2C and PSP battle, had issues with management over CBA violations and delays in salaries, had been expecting reprisals from the pro-PSP Board of ALECO. In fact it had a pending notice of strike that would prevent management from resorting to anti-union acts, including union-busting and possible lock out upon takeover by San Miguel. And when anti-union acts by management became imminent, the union went on strike on September 23, 2013.

Meanwhile on December 21, 2013, member-consumers occupied the ALECO offices and took back the cooperative by removing the Interim Board of Directors (IBOD), rejecting the PSP, electing a new IBOD, and declaring boldly that ALECO rightfully belongs to Albayanos. The striking workers and member-consumers are still holding out, as of this writing, and have vowed to prevent a San Miguel takeover at all cost.

Again, with the government clearly on the other side, workers and consumers were forced to defend their rights, all by themselves.

There are of course numerous, untold, and even more tragic stories on how the government left workers out in the cold while pampering investments with so much rewards and entitlements. But I have given more emphasis to the PALEA and ALECO cases because they are the most recent and are likewise good examples to show how the government is failing to fulfil its obligations in giving labor full protection and in addressing the country’s decent work deficits as defined by the ILO.

The ILO’s Decent Work Framework are filled with big words to back its objectives of giving the world’s people the opportunity to live a life of dignity even under the situation where market practically reigns over the world of work. Our view in Partido ng Manggagawa, however, is when government sides with capital in this era of globalisation, it would not only fail to provide people with decent jobs but will, likewise, become a witting or unwitting a tool in facilitating the proliferation of precarious work.

The Decent Work Framework

The Labor Department’s Institute for Labor Studies (ILS) pointed out that long before the ILO introduced decent work, the Philippines already had a comprehensive program for labor that centered on labor relations, labor standards and employment which, more or less, bore the essential elements of the decent work agenda – although not crafted in such a comprehensive and coherent manner as the current framework. This was enshrined in the Philippine Constitution, the Labor Code, and in administrative rules and regulations that sought to provide a framework for labor-management relations, workers’ welfare and protection, employment promotion and manpower development.

Hence when the ILO launched this program in 1999, the Philippines joined several other countries in the forefront of piloting its implementation. Since then, the Decent Work Framework has been adopted as the guiding principle in the implementation of the country’s labor and employment program.

The primary goal of the ILO under its Decent Work Framework is to promote opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work, in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity. This is in recognition of the fact that globalization creates insecurities and rising unemployment.

Decent work has four pillars which correspond to the four strategic objectives of the ILO:

-

respect for fundamental rights at work

-

creating employment opportunities for all

-

social protection

-

social dialogue

In its 2008 Decent Work Status Report, DOLE’s ILS presented in detail how decent work is going to be pursued. To paraphrase:

The first pillar demands that all those who work have rights at work. It calls for the improvement of the conditions of labour, whether organized or not, and whether work might occur, whether in the formal or informal economy, whether at home, in the community or in the voluntary sector (ILO, 1999).

The second pillar sustains the defense of rights at work which necessarily involves the obligation to promote the possibilities of work itself. It carries with it the responsibility to promote the personal capabilities and to expand the opportunities for people to find productive work and earn a decent livelihood. It seeks to enlarge the world of work, not just to benchmark it. It is, therefore, as much concerned with the unemployed, and with policies to overcome unemployment and underemployment, as it is with the promotion of rights at work. An enabling environment for enterprise development lies at the heart of this objective.

The third pillar calls for protection against vulnerability and contingency. It lays down the responsibility to address the vulnerabilities and contingencies which take people out of work, whether these arise from unemployment, loss of livelihood, sickness or old age.

The fourth pillar is the promotion of social dialogue. Social dialogue requires participation and freedom of association, and is therefore, an end in itself in democratic societies. It is also a means of ensuring conflict resolution, social equity and effective policy implementation. It is the means by which rights are defended, employment promoted and work secured. It is a source of stability at all levels, from the enterprise to society at large.

Furthermore, entrenched in these four pillars are the six dimensions of decent work, which conceptually represent the essential attributes of work, both quantitative and qualitative, that are being addressed by the ILO (Anker, 2002). These are:

(1) Opportunities for work – persons who need work are able to find work that covers all forms of economic activity including self-employment, unpaid family work, wage employment in both formal and informal sectors;

(2) Freedom of choice of employment – work should be freely chosen and not forced on individuals; bonded and slave labor as well as child labor are unacceptable and should be eliminated; it also means that workers are free to join workers organizations;

(3) Productive work – workers should have acceptable livelihoods for themselves and their families;

(4) Equity in work – women and men need to have equality of opportunity and treatment in work; it encompasses absence of discrimination at work and in access to work and ability to balance work with family life;

(5) Security at work – safe workplaces should be ensured and workers’ health, livelihoods and pensions should be safeguarded; there should be provisions for workers and their families for adequate financial and other protection in the event of health and other contingencies; it also recognizes workers’ need to limit insecurity associated with the possible loss of work and livelihood; and

(6) Representation at work – workers should be treated with respect at work; they should be able to join organizations to represent their interests collectively, free to voice their concerns and participate in decision-making about their terms and conditions of work.

The first two conceptual dimensions are concerned with the availability and acceptable scope of work. The other four dimensions are concerned with the extent to which work is decent or the quality of employment.

This is indeed a very ideal framework to pursue. But how did the Philippines fare since this framework was adopted in the Medium Term Philippine Development Plan (MTPDP) for 2001-2004; the National Plan of Action on Decent Work in 2002; and in President Aquino’s Philippine Labor and Employment Plan for 2011-2016?

Nation of ‘endos’

The case of PALEA represents the picture of how ‘endo’ (local colloquialism for “end of contract”) or contractual employment, in its worst form, has become the new face of labor in the country. Contractualization, everybody in the industry knows, is the most systematic way to undermine or suppress labor rights, as it has effectively rolled back everything the labor movement has gained over a century of struggle for security of tenure, safe working conditions, freedom of association, as well as the right to collectively bargain and to strike.

It is also an acknowledged fact that contractualization created the anti-union environment not only in designated economic zones (EPZAs) but in every industry, most particularly in manufacturing, services and agricultural production. Under the law, contractual workers are not allowed to join the rank-and-file union. This is the reason why only 200,000 out of the 20 million wage workers are covered by collective bargaining agreements (CBAs). Without the unions to represent the workers, the fourth pillar of decent work – social dialogue – had become a big, bad joke absent the conditions of freedom. The particular case of ALECO is an example of failure of social dialogue – when powerful forces succeed in blocking the democratic, worker-consumer led initiative.

In 2004, the Bureau of Labor and Employment Statistics (BLES) reported, based on its own survey, that one in every three of the country’s employed people are considered ‘non-regular’ – in other words contractual, casual, or those whose work fall under varied forms of temporary employment. ILO’s own study in February 2010 found that the rate of contractualization in the Philippines has significantly risen, with 70% of the workforce without written or formal contracts.

Contractualization is anathema to decent work. Yet despite the adoption of the decent work framework, the ’endo’ regime in the country is on the rise and the government is often caught idle, if not party to the outbreak, of this scourge.

Jobless growth

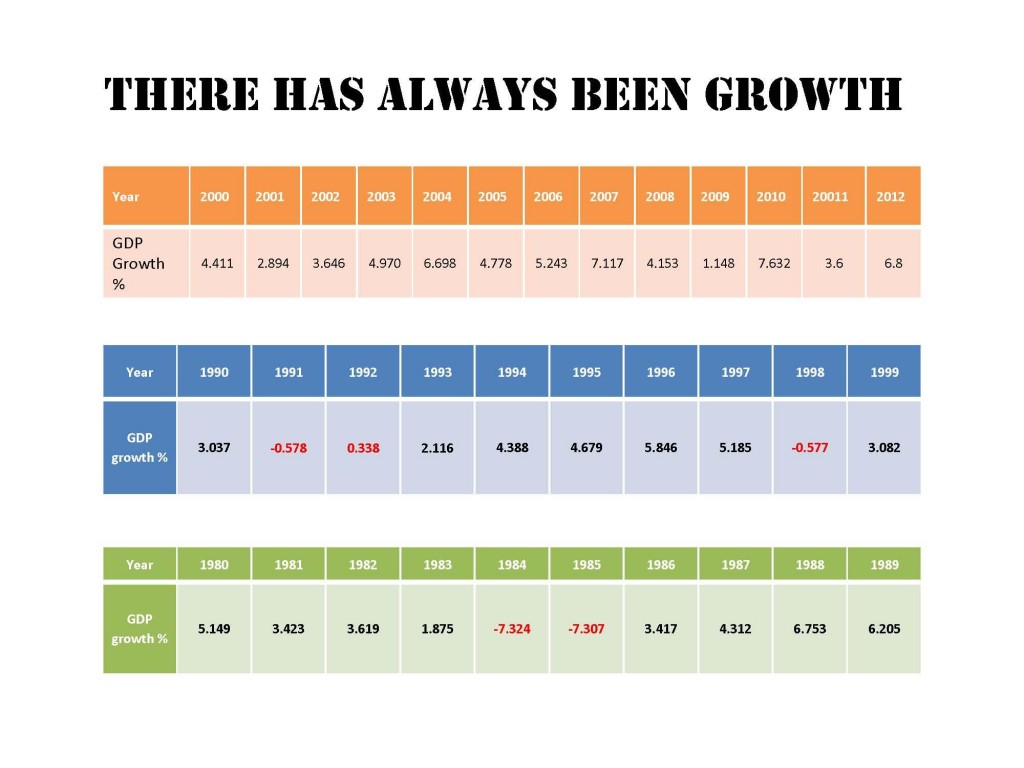

In a previous paper, “The Growth of Inequality”, I tried to trace back the country’s growth years in the span of three decades. Except for crisis years 1984-85 (the height of the anti-Marcos struggle), the power crisis of 1991-92, and the Asian financial crisis of 1998, Philippine growth had been generally positive, with the last decade – 2000-2012 – registering the highest average (see Table below).

Yet employment remained stagnant over those years, bolstering the claim that Philippine growth remains not only unequal but also accompanied by marked joblessness. The only time the country achieved a single digit unemployment rate was in 2005, when the government redefined the ‘unemployed’ by excluding from the list those who are unemployed but are not available for work. That rendered some 1.4 million Filipinos invisible in the unemployment data (see Table below).

It is unemployment that likewise drives poor people, including their children, to hop from one hazardous and unsafe type of work to another. The country still has 5.5 million child laborers, according to the National Statistics Office (NSO).

Moreover, the ILO has also taken notice of the growing unemployment among young people aged 15-24 accompanied by high proportion of youth, particularly young women, who are neither in school nor in employment.

Unfortunately, both under Gloria Arroyo’s MTPDP and PNoy’s PLEP, no coherent industrial plans were laid down to radically address the country’s chronic unemployment problem. All that they have in common is the predilection to develop small enterprises (SMEs) as strategy in creating employment. The Philippine Employment Service Office (PESO) program for LGUs, on the other hand, is largely unfunded.

As the ILO has pointed out, despite the Philippines having declared full employment as a policy and having ratified Convention 122 (Employment Policy Convention), this enabling policy on full employment has not translated into job creation.

Lack of social protection

The ILO’s own report had puts in details the lack of social protection for a great number of Filipinos. Lack of jobs and the predominance of vulnerable employment characterize the Philippine labor market, thus the need for a wide range of social protection especially in the face of worsening climate crisis. This is a basic human right and in the words of ILO, “a means to foster social cohesion, human dignity, and social justice.”

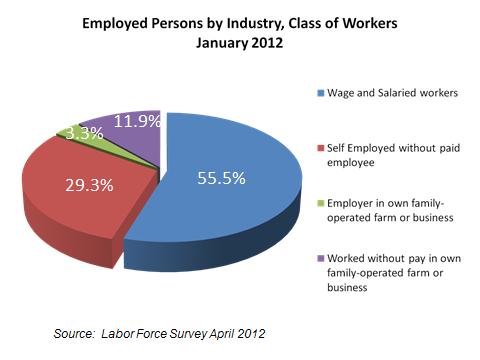

The Labor Force Survey in January 2012 showed that close to half of Filipinos are in vulnerable employment, which is defined as the sum of own account (self-employed) and unpaid family workers. This is on top of the unemployed persons who chronically belong the poorest of the poor (see Table below).

Self-employed and unpaid family workers lack access to social security and other entitlements that are usually attached to formal employment such as medical care, sickness and disability benefits, unemployment insurance, maternity benefits, and old-age pension, among others. But not all these are available to formally employed persons. The ILO said only 25% out of 38 million workers are covered by social insurance (under SSS and GSIS programs) in the public and private sector.

The Philippines until now has no unemployment insurance scheme, leaving workers helpless during temporary or unexpected job loss. And except for limited Philhealth coverage, the country has no universal healthcare program that is available to all, whoever and wherever they are, whenever they need it.

Experiences have shown that social protection is achievable even in developing countries, as in the case of Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and other Latin American countries. India for its part was able to enact an employment guarantee program – the National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (NREGA) which provides rural unemployed population a guaranteed 100-day employment in a year with minimum wages.

The Philippines, however, is a certified laggard in this respect, unmindful of the consequences this lack of social protection impacts on poverty, inequality and human dignity. What it has is a stand-alone and a poor copy of Brazil’s conditional cash transfer (CCT) scheme which is not in any way related to employment or poverty-reduction program.

Women still most vulnerable

In March 2009, we at PM published a special article on women, debunking what the Secretary General of the National Statistical Coordinating Board (NSCB), Dr. Romulo Virola, declared as the reversal of status between men and women in the Philippines. According to Virola, it is now Pepe who is catching up on Pilar.

In his report, “When will Filipino men catch up with Filipino Women?” Virola mockingly called on Filipino men to campaign for “empowerment” and consider holding their own “National Day for Men” since women have overtaken them already. For us it was folly and an attempt to artificially place women on top of men by using select statistics to fit into this hypothesis. This is no different from DOLE declaring the phenomenal ‘zero’ strike as the success of social dialogue and tripartism.

Virola said that based on a study conducted in 2003, women outdid men in terms of development in 72 out 79 provinces of the country. Women in Zamboanga del Norte got the highest advantage with (2.1735) GER or Gender Equality Ratio. It was followed by Biliran (2.0644), Surigao del Sur (1.8111), Apayao (1.7066) and Abra (1.694). On the other hand it was still men’s world in Maguindanao (0.0206), Siquijor (0.0222), Basilan (0.3935), Sulu (0.8491) and Benguet (0.9202).

The study declared that from 2000 to 2003, women have overtaken men in terms of health, education, and even in income. That was great news, indeed, and we must salute women for doing all they can to lift their individual status in life. But it is plain misleading for Virola to declare that equal opportunity between men and women in the country has already been achieved. This is totally wrong.

Hidden in Virola’s report were the more important numbers that show the gaping inequality between Filipino men and women. In 2009, according to the Labor Force Participation Rate (LFPR) survey, only 49.4% (14.7 milion) of women were active participants in the labor force compared to 78.6% (23.17 million) for men or a gap of 29.2%. Women LFPR went up to 50.4% in 2011 but it dropped again to 49.6% in October 2012.

Where, then, are those women who are not active members of the labor force? Half of them, those under age group 15-19, may be in school and those above 60 may have already retired. But there are more than 11 million, with ages 20-59, who are supposed to be active members of the labor force. So, where are these women?

They are at home doing visible but economically unquantified domestic work. They are not included in statistics for unemployed women because counted are only those who are actively looking for jobs. This is the reason why only 1 million women are considered “unemployed” out of the 3 million total. This merely confirms an ILO report which states that more than half of Filipino women age 15 and above have no income of their own. In other words, women are still the most vulnerable sector in Philippine society.

More women graduate from schools compared to men, yet majority of them end up absorbed not by industries but by domestic work. Women may have lower mortality rate now than men, yet more and more women die each day with the further delay in the implementation of the reproductive health law.

There are good stories to tell about Filipino women getting on top in many fields, including in business and politics. But the truth cannot be denied that majority of Filipino women still suffer the life of Pilar – poor and oppressed.

The workers’ way

According to ILO, “Employment opportunities helps represent opportunities for work, and unacceptable work helps represent work in conditions of freedom. Adequate earnings and productive work help represent productive work. Fair treatment at work, balancing work and family life, and social dialogue help represent equity and dignity at work. Safe work environment, social protection, and stability and security of work help represent security at work.”

Decent work therefore is a goal that is hardly achievable without the government leading the charge against the reigning environment created under the market-driven processes of globalization. The Philippines was picked out as one of the pilots in ILO’s decent work. But what decency can we show the world when we are, in fact, degenerating into a nation of endos; of poor and hungry people; of smothered labor rights; of jobless growth? What did we achieve when gaping inequalities between the rich and the poor and between men and women of this country still exist?

Workers, business and their governments, as conceived by the ILO, were supposed to be social partners in realising the objectives of decent work. That is sadly not happening here in the Philippines. In most cases, it is business and government that denies workers the free exercise of their freedom, of their constitutional rights. No wonder despite being the pilot implementer of the Decent Work Framework, the country failed to trim down its decent work deficit over the last 12 years.

So whenever there are successful stories in pursuit of decent work here, it is nether the government nor business but the labor movement that has been trying to narrow down the gap by defending and promoting labor rights the workers’ way – through struggles and resistance.

———————————————————-

References:

-

The PAL-PALEA Settlement Agreement, 14 November 2013

-

PM Press Statements on PALEA struggle

-

Manifesto, ALECO Member-Consumers, 21 December 2013, provided by Alliance of Progressive Labor

-

The ILO Decent Work Framework

-

Decent Work Country Profile The Philippines, ILO,2012

-

Riguer, Institute for Labor Studies, 2008, Decent Work Status Report: The Philippines

-

Wilson Fortaleza, August 2013, Growth of Inequality presentation

-

News articles on child labor

-

NSO, Labor Force Participation Rate and Men-Women Participation Gap by Sex, 1998-2012

-

Workers’ Digest, Lamang na nga ba si Pilar kay Pepe?, Partido ng Manggagawa, March 2009,